Viña Delmar, Flapper Fiction, and Snappy Stories Magazine

Today’s guest-post is by David Earle, Professor of Modernism and Print Culture and Chair of the Department of Art & Design at the University of West Florida. (See complete bio below.)

Bobbed-haired Viña Delmar in a 1929 promotional photo from Writer’s Digest, October 1929.

One hundred years ago today … “Tony Steps Out,” Viña Delmar’s first story, was in the latest issue of Snappy Stories magazine, beginning a five-year partnership that, until it folded in 1927, would help make Snappy Stories the preeminent working-class venue for Flapper Fiction and Delmar one of the most prolific proponents of flapper stories. Both magazine and author geared their stories to the burgeoning population of working women who in 1922 were flocking to New York City in search of careers and independence.

During the 1920s, job opportunities for women expanded and diversified. Between 1910 and 1930, the percentage of female office workers alone in New York City grew 500% (Curtis 885). According to the 1920 census, there were over a million women workers in New York City and surrounding boroughs in trade, manufacturing, clerical, domestic, and professional positions. The editors of Snappy Stories consciously sought out this audience.

Cartoon of a coed reading Snappy Stories from the yearbook of the Lakeview High School, Chicago, 1923

Since 1912, the magazine had evolved from a general fiction magazine to one that specialized in cosmopolitan fiction and situational romances aimed at both a female audience and a burgeoning youth culture. In 1914, when the magazine had a print-run of over 200,000, the publisher W. M. Clayton described its contents as “not such that would interest the poorly educated,” but rather geared to “homes of culture and refinement, especially to the women of the big cities. We do not reach the country women; farmer’s wives are not interested in fiction, or at least in the kind of fiction that ‘Snappy Stories’ gives…” (Clayton 61). The following year, the magazine would run advertisements in Vogue, giving us an idea of its aspirational audience, yet the magazine was unquestionably a “pulp,” hence had a much more diverse and working-class audience than Vogue. Starting in 1917, allusions to Snappy Stories as favorite reading material started appearing with more and more frequency in high school and college newspapers and yearbooks. The magazine had found a key demographic, which they increasingly catered to with the advent of the Jazz Age.

By 1921, under the new ownership of George Delacourt and editorship of Lawton Mackall, Snappy Stories had fully embraced the cultural shifts of modernity. Unlike the “clean” stories in the romance pulps like Street and Smith’s Love Story Magazine that were just starting to appear on the newsstands, Snappy Stories leaned into the changing morality of the post-war generation. In writing trade journals, they called for stories “with lots of ‘go’ in them – stories that have a decided sex interest, but which keeps within the bounds of good taste” (Writer’s Digest 16). The magazine started the “Jazzbo’s Jottings” column, a review section of popular songs, ragtime, and early jazz. John Held, whose artwork became synonymous with the flapper movement, was a frequent contributor throughout the mid-1920s.

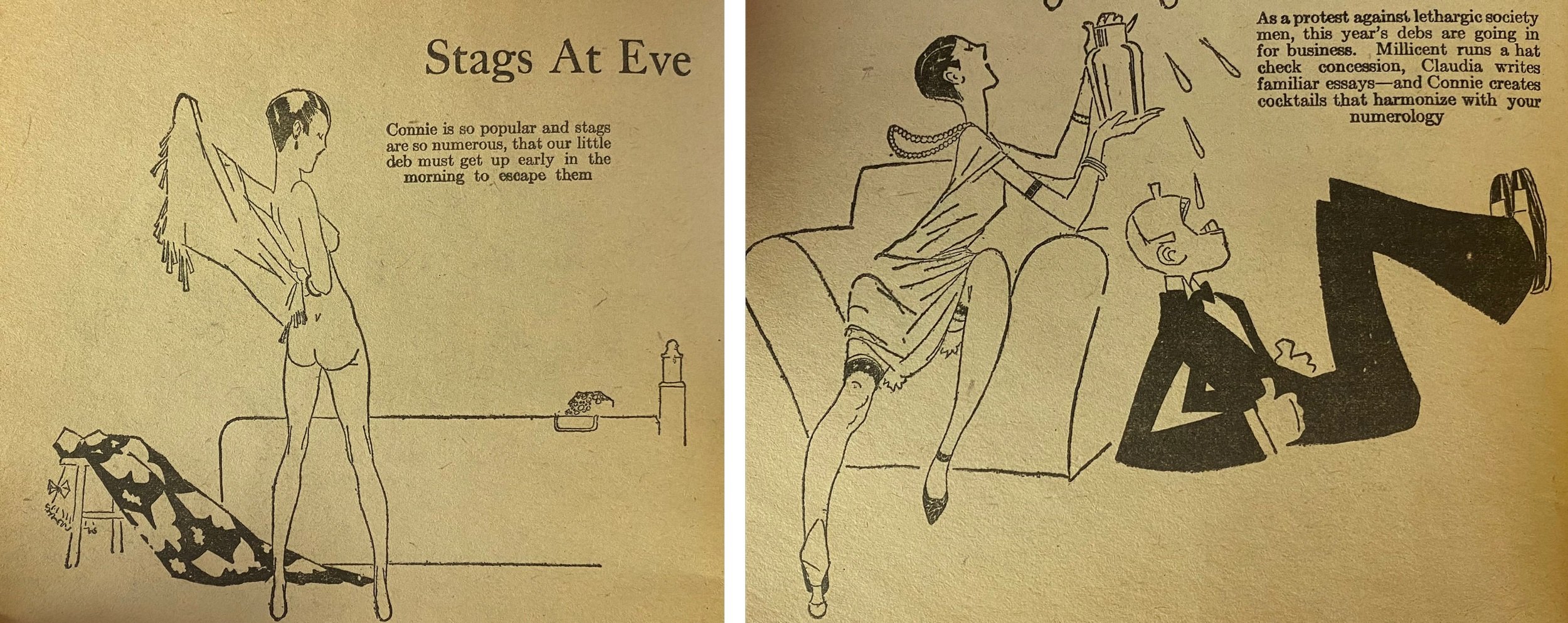

Cartoons by John Held, Jr. from Snappy Stories, February 1926. His cartoons here are much more risqué

than those found in magazines like Life or College Humor.

And from 1922 on, the magazine purposely courted young female authors who could identify with the flapper movement (“Interview” 9). Many of these authors, like Christine Dale and Dana Ames, are long forgotten but some went on to literary stardom. These “Flapper Auteurs” include Delmar, who first appeared in the December 16th issue; Dawn Powell, whose first story would appear the following month; and Katharine Brush, whose first story appeared in January 1924.

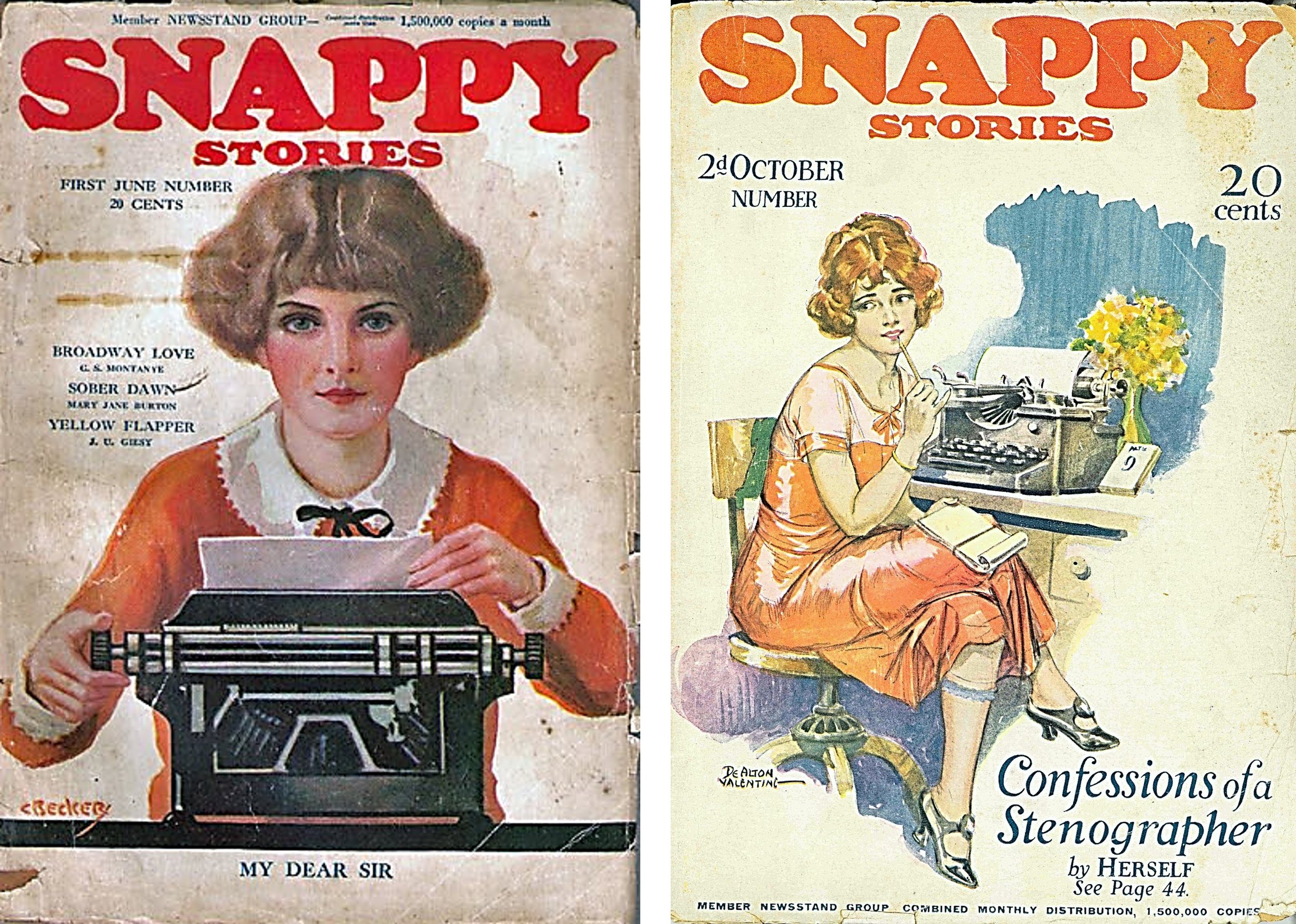

Snappy Stories, June 1923 (C. Becker) and October 1924 (DeAlton Valentine).

Snappy Stories specialized in what can best be described as Flapper Fiction: situational romances that often revolved around young women learning about or well-versed in navigating the urban landscape of offices, Broadway, Greenwich Village, or Paris. They are office workers, debutantes, chorus girls, artist models, and gold diggers who indulge in jazz, cocktails, and casual flirtations. Premarital sex was often alluded to, sometimes celebrated. Unlike the traditional romance formula, the stories do not always end in marriage (though many of them do). The magazine catered to both a male and female readership since, like the public image of both the flapper and female office worker, it negotiated between themes of objectification and female empowerment. This dichotomy is readily seen in both contents and cover designs. Covers often featured women as telephone operators and typists, but also, of course, negligee-clad chorus girls and artist’s models.

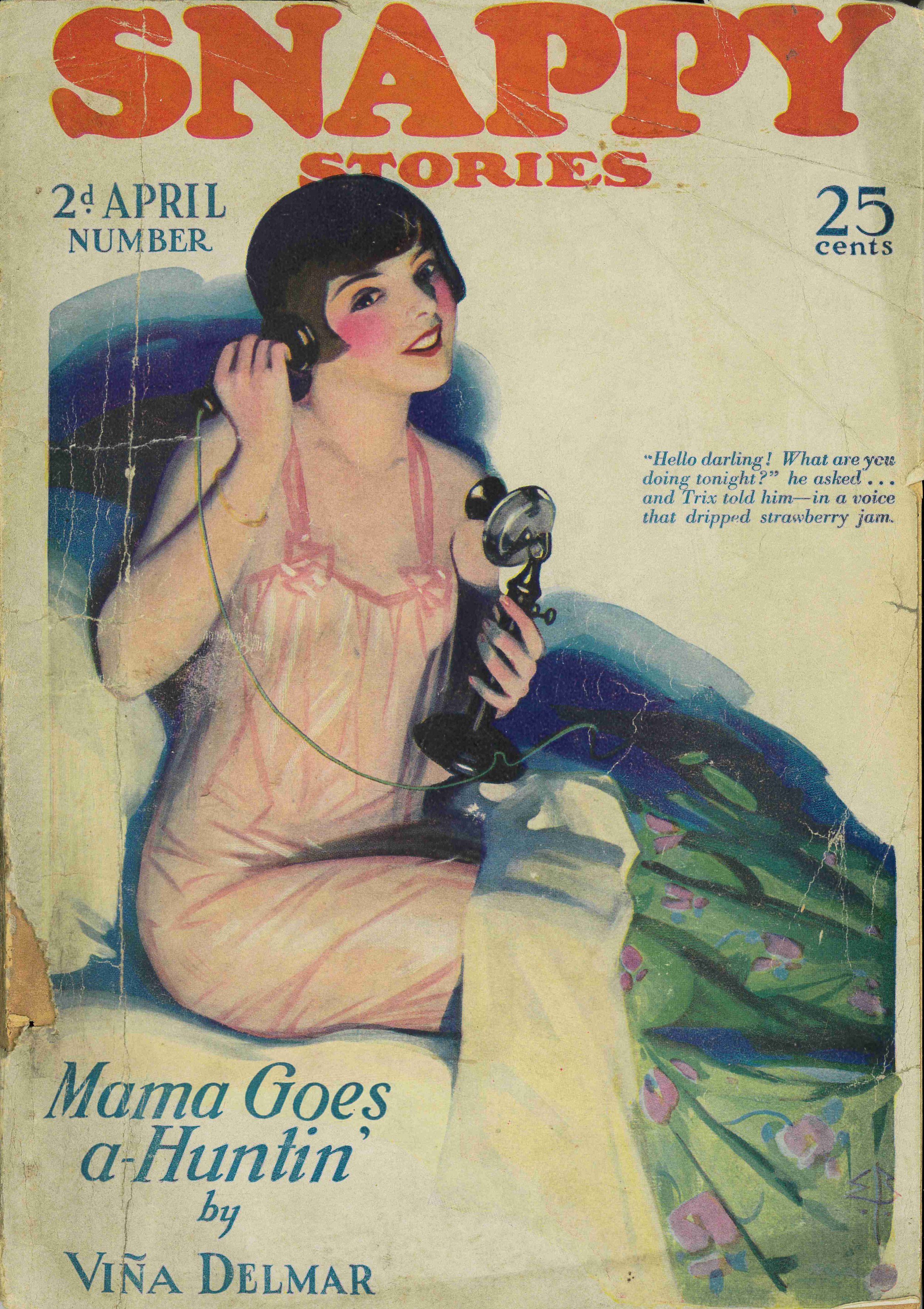

Snappy Stories, April 1925 (Enoch Bolles) – purportedly modeled on Delmar.

Delmar, a young, bobbed-hair Brooklynite, whose parents performed on the Yiddish vaudeville circuit, personified the New York flapper for Snappy Stories. After her first appearance in 1922, Viña Delmar quickly became one of the magazine’s most popular authors, writing 85 stories between 1922 and 1927, and even earning a regular gossip/literary column, “Viña Delmar says—." Many of her cover stories featured the same dark-bobbed flapper, modeled on Delmar herself.

Much of her success is due to her fast, clever dialogue and her “line” – the humorous quips and clever tones of her stories. At times, her narrative voice breaks the wall between reader and writer, self-reflexively drawing attention to her own formula, as in “Know Your Man,” from 1924: “Years ago, long before I even owned a pencil, Doris’s parents had shown great forethought by passing out of this story making it unnecessary for me to describe them. I shall, however, state that as bootlegging was not a popular industry then, Doris’s father had been a doctor…” ( Delmar, “Know your man” 5).

Delmar’s familiarity with the emergent professional class of women office workers also contributed to her success; she was writing to her audience. Her first story, “Tony Steps Out,” for example, features a heroine who supports her family by directing “the destiny of an office on Times Square,” but she is so “engrossed in business that she never gave men a thought.” When Tony does fall, it is for a drunken and abusive scenario writer. She eventually snaps out of love and returns to her old, strong-willed, and capable ways. The story balances a healthy dose of social realism with snappy dialogue, a formula which Delmar would stick to in Bad Girl, her novel about the love life of a telephone operator that became the best-seller of 1928.

Delmar would go on to write fifteen more novels as well as Broadway plays, screenplays (she was nominated for an Academy Award for The Awful Truth), and dozens more short stories. Today, though, she is largely forgotten, as is Snappy Stories. Both are lost voices of the Jazz Age, well worth rediscovery.

– David Earle, December 16, 2022

David M. Earle is a Professor of Modernism and Print Culture and Chair of the Department of Art & Design at the University of West Florida. He has published extensively on the history of magazines and modernist literature. His edited collection of flapper stories, "Where All Good Flappers Go..." Essential Stories of the Jazz Age, will be published by Pushkin Press in June 2023. Take a look at his Boozehounds and Bookleggers Blog.

References/Further reading:

Clayton, W.M. Printer’s Ink, 3 September 1914.

Delmar, Viña. “Know your man,” Snappy Stories, 5 July 1924.

“Interview with Viña Delmar.” The Hartford Courant, 1 January, 1953.

Simon, Curtis. “The Supply Price of Labor During the great Depression,” The Journal of Economic History 61. I4 December 2001

Writer’s Digest 1.9, August 1921, p. 16.

TAGS: women writers, women's history, gender, flapper, feminist, fashion, style, periodical, pulp, magazine, modernism